Bottled Songs - an Interview with Chloé Galibert-Laîné and Kevin B. Lee

My Crush Was a Superstar, from Bottled Songs

What is Bottled Songs?

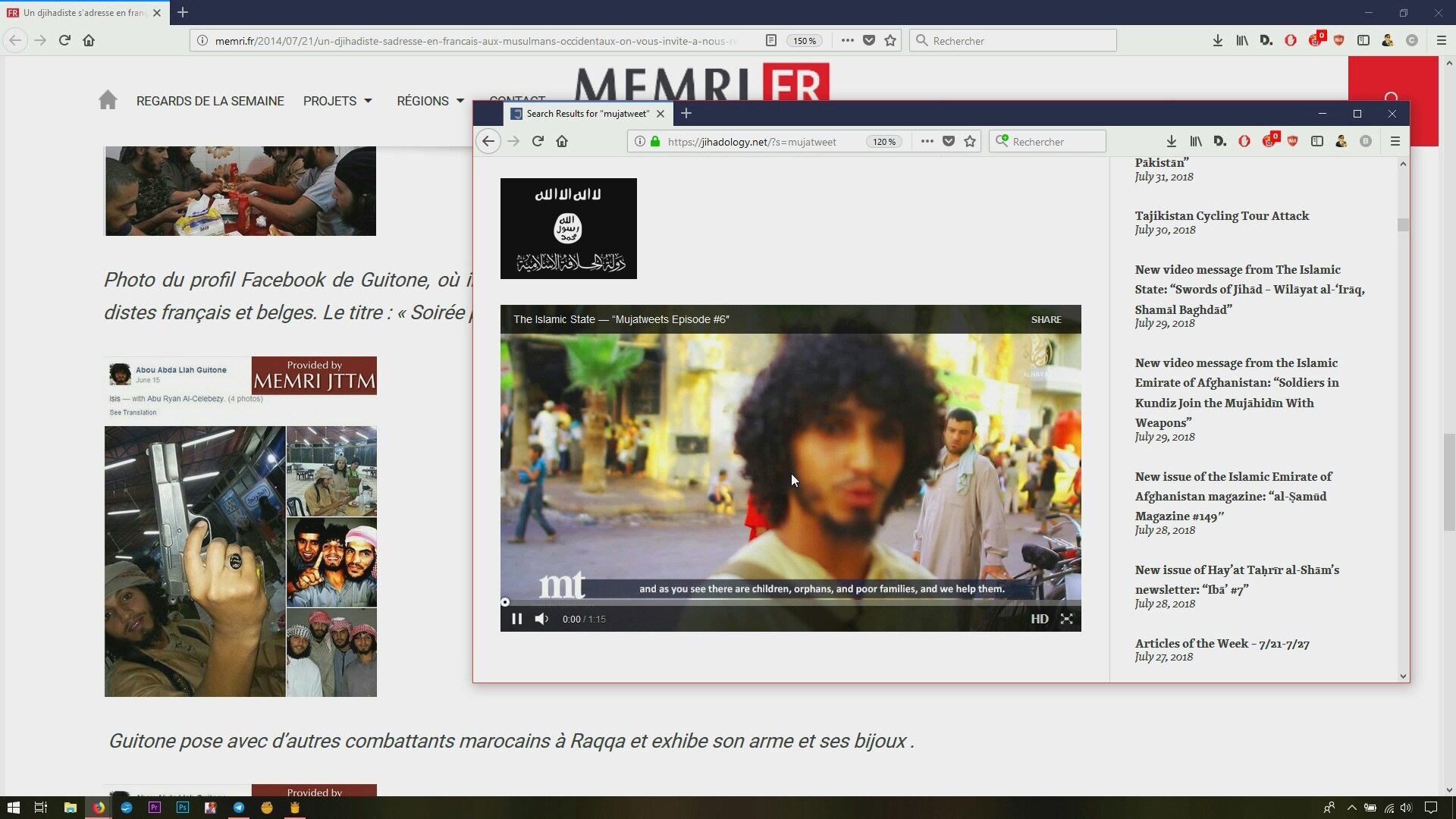

Bottled Songs is a series of video letters documenting our investigations of online media related to ISIS. These “desktop epistolaries,” recorded from our computers, depict our experiences navigating through an unstable virtual environment of fear and attraction. The epistolaries examine a range of subjects connected to ISIS media: specific videos produced by ISIS; spectral figures who appear in the videos; and viewers of the videos with a diverse range of motivations and interests. These investigations combine to give a multifaceted account of the images, people and networks that make up an unruly sphere of online terrorist media.

Why do you adopt the form of “desktop epistolaries”?

The desktop is the native environment of the media objects, networks and practices that we analyze. We aren’t just researching videos and images, but the interfaces through which they are found and experienced, and other artifacts that inform their meaning, such as comments, view-counts and links. We use screen recordings as a method of online ethnography.

As to the epistolary form, it is an organic outcome of our process: it reflects the way we communicated with each other during the first year of our collaboration. We decided to make this interpersonal mode of address a defining characteristic of our work, because it enables a greater accountability towards our own subjective and affective responses to these media. It allows us to disclose an intimate realm of fears, anxieties, attractions and associations that these media elicit from us.

But then, what does it mean to make this private exchange public? Our research has made us sensitive to the degree to which online searches relating to ISIS are closely monitored by the authorities, a condition that also informs the online practices of our subjects. The illusion of privacy in an online environment became something that had to be explored in the work, and the desktop epistolary form reflects this duality of privacy made public.

What are the origins of this project? How did you become interested in this topic?

This collaboration reflects the evolution of our respective research interests. Kevin, who has a longstanding practice in video essays as a mode of online film criticism, now investigates how the cinematic operates within online media operations, performing a vital role in shaping the audiovisual geopolitics of social media. Chloé, who is a researcher in film studies and sociology, explores modes of spectatorship and gestures of appropriation in cinema and new media. After the 2015 attacks in Paris, she started researching online terrorist media and the various contexts in which they are watched and re-appropriated, following the work of scholars such as Cécile Boëx and Dork Zabunyan.

In 2016 we began a series of email exchanges discussing the possibility of applying videographic methods of image analysis to ISIS videos. We wanted to document our spectatorial responses to their audiovisual rhetoric, trace their spread across different media and platforms, and reflect on how they had acquired an aura of abject terror, even among those who had never watched them.

How did you choose your subjects? How do you coordinate your investigations of them?

We each identified a set of subjects or figures of interest. We feel that we didn’t choose our subjects so much that the subjects chose us. Our project tries to account for what factors beyond our own agency informs our desires to engage with these subjects. These factors can be defined as algorithms: computational, societal, personal. They range from the algorithms of online search results to our own sociological and psychological predispositions towards certain media figures and images.

While we each have our self-selected subjects to research, the process of conceptualization, writing and editing is collaborative. Each video is narrated by a single voice, but in fact all the videos are co-authored. The dialogical structure of the videos emphasizes the contrasts in our interests and approaches to our subjects, as well as differences in our respective use of the desktop epistolary form.

How would you describe your research method and production process?

Our research method involves extensive periods of online research, followed by a period of writing and screen recording that documents, narrates and reflects critically upon our research. It is never a literal process of reproducing our research experiences, but a continual negotiation between how the research was actually conducted and what is most interesting to present within a narrative framework.

As we became aware of the internet as the site of countless research operations, we adopted the term “simulation” to describe our own method. To what extent are our gazes simulating other gazes on the same images? The gaze of a potential recruit, a terrorist, a journalist, an NGO worker gathering evidences of war crimes, or any other internet user who encounters ISIS media online? We want our activity to depicting the desktop as a site for an endless array of unseen searches.

At the same time we do not claim to speak for anyone other than ourselves. For this reason we term our investigations “poor simulations.” ‘Poor’ in the sense of the modest means of our research, stringing together bits and pieces of data. ‘Poor’ - to recall Hito Steyerl’s reflections about the politics of “poor images” - in the sense that our investigations don’t produce economically or militarily valuable insights about our subjects. ‘Poor’ in the sense that our research is not conducted with an air of professional authority, as it contains false leads, unscientific methods, misdirections and dead ends. But these qualities of poorness bear values of their own. They reflect the poorness of the everyday knowledge acquisition online, in all its perilous messiness. Rather than delivering facts in an impeccable package, we are more concerned with unpacking the truths within our own efforts to understand.